As part of our Sarnia Remembers series — now in its eighth year — The Journal is publishing a series of stories this week, honouring veterans and fallen soldiers from Sarnia-Lambton.

By Tom St. Amand and Tom Slater

By Tom St. Amand and Tom Slater

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill told air crews that tonight's operation was one they would share with their grandchildren one day. But at 2040 hours, as his Halifax bomber flew into the darkness from RAF Lossiemouth in north-east Scotland, Sarnian John “Bunt” Murray figured he wouldn't live to see tomorrow. Along with his six other crew members aboard Halifax W1041 ZA-B, Bunt knew their 2,300-kilometre flight to Norway was “a suicide mission.”

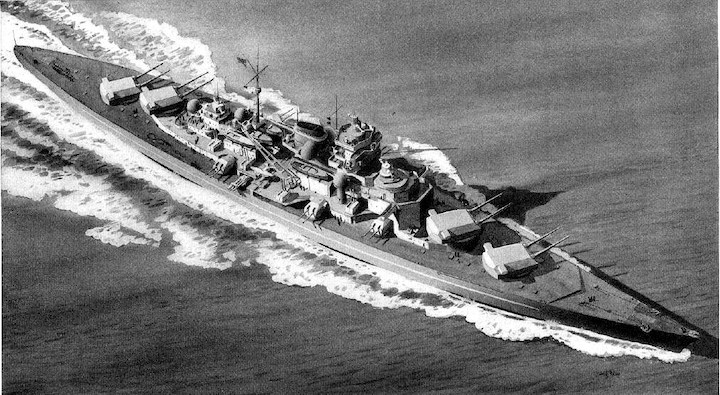

It was Monday evening, April 27, 1942. As part of RAF 10 Squadron, Bunt's Halifax was one of 43 bombers attempting to sink the Tirpitz, Germany's formidable battleship and sister ship to the Bismarck that the British Navy had sunk the previous May. She had been anchored and hidden in a fjord near Trondheim, Norway, for nearly four months. In late January, an Allied reconnaissance plane had found her, photographed Tirpitz's specific location, and a relieved Churchill saw his chance to “turn the tide of the war.”

For Churchill, nothing was more imperative to the Allies' war effort than sinking or crippling the Tirpitz.

Hitler called the Tirpitz the “pride of the German navy” and with good reason. No ship was as formidable and intimidating. Stretching over 823 feet in length and run by a crew of 2400 men, Tirpitz reached speeds of 34 knots and was faster and more powerful than any Allied warship. Her eight 15” guns had a range of 13 miles and each shell weighed nearly a ton. Tirpitz’s armament also included twelve 5.9” secondary guns and over 40 anti-aircraft guns. With thick 4” armour encasing the decks, hulls, turrets, engine room, and magazines, conventional bombs bounced off it.

The Germans declared her unsinkable.

The potential damage Tirpitz could inflict on Allied ships had created a sense of urgency in Churchill. Even though the battleship was berthed in Norway, 70 kilometres from open water, her mere presence threatened the vital sea lanes of North Atlantic and Arctic convoys. At great expense, the Royal Navy altered convoy routes to bypass Tirpitz, and carriers laden with tanks, aircraft, trucks, and ammunition bound for Russia required four times the number of escorts for extra protection. Wolf packs of U-boats had been feasting on enemy ships for the last 18 months. Allied warships were desperately needed to reduce U-boat successes in other theatres of war, but as long as Tirpitz loomed in Norway, convoy escorts remained in the North Atlantic. Churchill seethed privately about “the beast”, his nickname for Tirpitz, and admitted publicly that the battleship had created “a vague general fear.”

In desperation, Bomber Command had devised a risky plan in late January 1942 to attack Tirpitz at night as she lay anchored. The first two operations to sink her or to disable her had ended in disaster, but Churchill was not deterred. He ordered a third attack for late April and rationalized that the “loss of 100 machines or 500 airmen would be well compensated for.”

Aboard Halifax W1041, Bunt strapped himself into the wireless operator's seat in the nose of the bomber, just below the pilot and the bomb-aimer. Bunt must have been terrified. He had grown up on Durand Street, enlisted with a few friends from Sarnia in July 1940, and now, less than two years later at age 22, had volunteered for a vital operation fraught with danger.

At least the crew's pilot and squadron leader, Australian Donald Bennett, 32, inspired some confidence. Never afraid to challenge authority, the Aussie was experienced in long-distance flights and was regarded as a brilliant tactician and a superb pilot. Bennett, described by a fellow officer as having “a prickly demeanour,” said little as their Halifax crossed the North Sea; his crew sat quietly, prayed silently, and inevitably reflected on what awaited them.

They knew exactly where Tirpitz was and tonight's clear skies were ideal for flying. From his vantage point, Bunt noticed moonlight glittering on the calm waters of the North Sea, and his crew would soon be seeing the hills and peaks of Norway's coast; however, Bunt knew the cloudless skies also meant the Germans would see them coming from the west, the only direction from which enemy airplanes had a chance of hitting the Tirpitz. This would not be a surprise attack.

Tonight's operation had two phases. The initial phase, which occurred a half hour before the second phase, involved Halifax and Lancaster bombers from 44, 76, and 97 Squadrons dropping 4,000-pound bombs from 6000 feet on the Tirpitz. Each plane also carried 500-pound bombs to destroy searchlight positions, thus rendering German anti-aircraft flak ineffectual.

They faced major obstacles, however. German radar detected any plane flying over 1,500 feet and a nearby aerodrome housed 60 Me 110 and Me 109 fighters. The bombers would be easy prey for these Messerschmitts. They also had to evade a network of anti-aircraft stations on the slopes surrounding the battleship as well as Tirpitz's powerful guns.

Bomber Command knew bombers in the first phase had little chance of harming the Tirpitz. Assuming they made it past the German night fighters and anti-aircraft stations, hitting the battleship was not impossible, but highly unlikely. At this stage of the war, navigational aids were primitive and bomb sights were simple and hopelessly inaccurate.

The Germans had also found the ideal location to anchor the Tirpitz. She was berthed in a narrow finger of deep water, three-quarters of a mile at its widest, and was tucked into the tail of an inlet which stretched only 350 metres across. Steep hills on three sides formed a natural barrier to guard the battleship. Anti-aircraft guns and searchlights were positioned on these surrounding cliffs. Tirpitz was also covered in grey camouflage nets that blended in with the dull-coloured area. As extra protection if needed, the Germans used chemical smoke generators on the slopes to create a thick protective pall which obscured Tirpitz within minutes.

As one pilot stated, bombing Tirpitz from 6,000 feet was like hitting “a slit trench” from that height.

By 2308 hours, radar stations had notified German officers of the first wave of approaching four-engined bombers and by 2330 hours, sailors aboard Tirpitz were at action stations. Shortly before midnight, the first bombers appeared and encountered heavy enemy fire. Powerful searchlights pierced the darkness and the skies lit up with trails of flak and bursts of flames. At the same time, German soldiers fed canisters of chlorosulphonic acid into the smoke generators and, within minutes, a dense blanket of smoke hid most of the battleship.

The first wave of bombers was setting the stage for the arrival of bombers from 10 and 35 Squadrons.

In Halifax W1041, Bunt Murray was girding himself for the most frightening time of his young life.

St. Amand and Slater are the authors of Valour Remembered: Sarnia-Lambton War Stories, available at The Book Keeper.