The Journal reviewed the most recent opioid surveillance data from Lambton Public Health (LPH) and Ontario Public Health data and spoke to local agencies grappling with the ongoing opioid crisis. In this special report, we provide a bigger picture of what’s happening in Sarnia-Lambton, and explore what more needs to be done.

OPIOID STATS IN SARNIA-LAMBTON

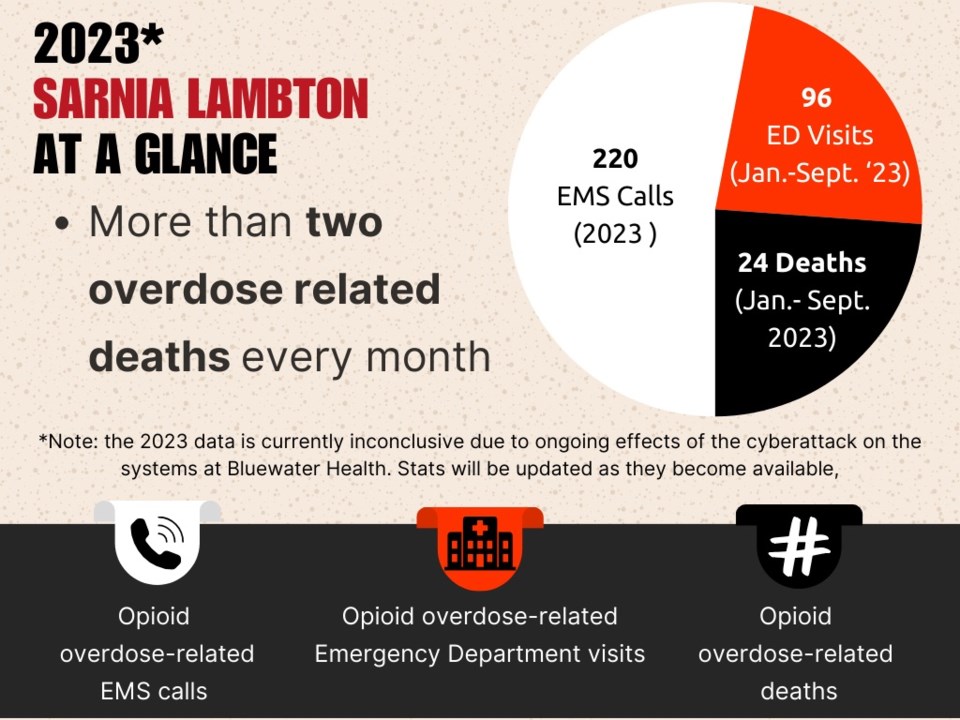

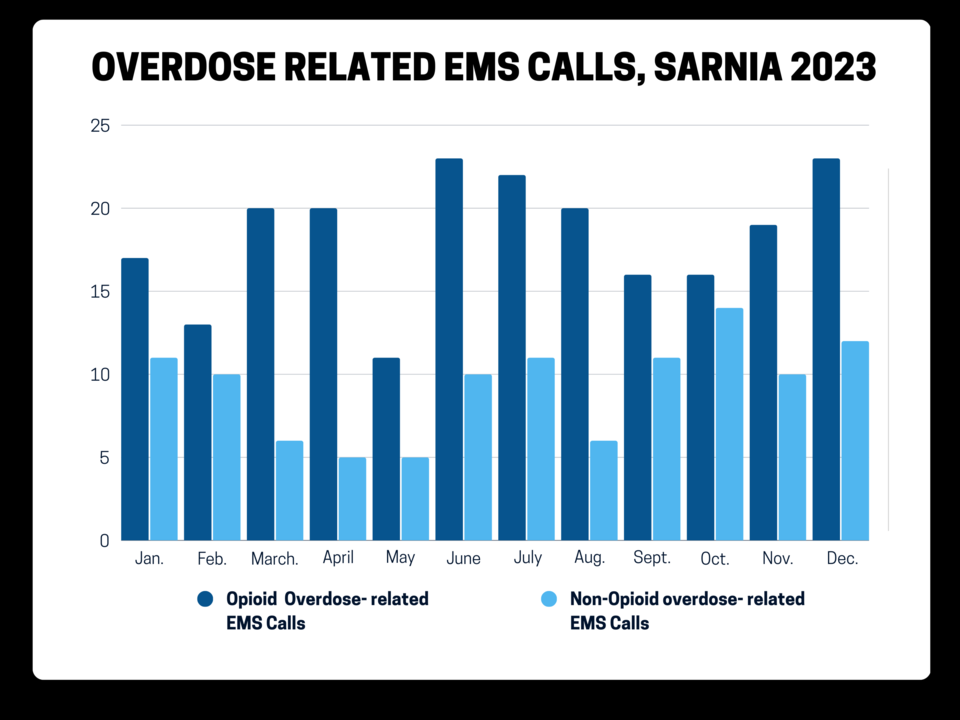

“The numbers are still high,” said Michael Gorgey, Manager of Health Promotion at LPH. He pointed to 24 opioid overdose related deaths in the first nine months of 2023 (Jan.-Sept., preliminary data), and 220 EMS calls for suspected opioid overdoses in total, last year. In 2022, there were 32 opioid-related deaths among Lambton County residents (preliminary data) and 240 EMS calls for suspected opioid overdoses.

INFOGRAPHIC: Opioid related overdose deaths in Sarnia-Lambton, 2018-2023

INFOGRAPHIC: Opioid related overdose ED visits, 2018-2023

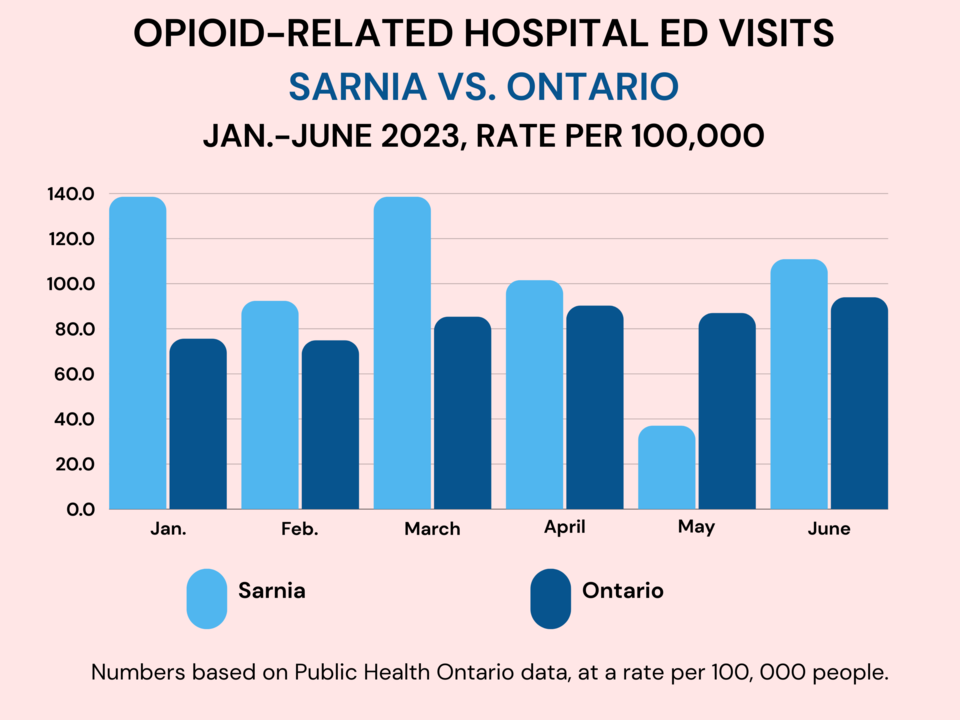

“Our rates are higher than the Ontario rate for both emergency department visits and EMS calls,” Gorgey said, noting nearly 100 opioid overdose related emergency department visits in the first nine months of 2023. “We have a bit of a data issue with 2023 because of the cyberattack [on Bluewater Health] so that data is a bit skewed… but, we are still talking about 96 emergency department visits over that span, which is in no way something we are proud of.”

Earlier this month, a spike in suspected opioid-related overdoses prompted LPH to issue an advisory — its first since July 2023 — following ten suspected overdose/toxicity reports over a five-day period.

Health units across Ontario are sounding alarms in the wake of opioid-related poisonings in recent weeks: the Brant County Public Health Unit issued a public safety alert in Nov. following 27 suspected drug poisonings and five deaths; Grey-Bruce Public Health issued a community alert after reports of six suspected opioid-related overdoses, including two fatalities, over a six-day period this month; officials in Belleville declared a state of emergency after reports of 17 overdoses in 24 hours on Feb 6; and officials in Durham are calling for immediate action from all levels of government in the wake of 127 calls for suspected opioid overdoses in the first six weeks of 2024.

“It’s a large issue that’s impacting this area and all areas,” Gorgey said. “We’re trying our best to make sure people who use drugs are aware when we get information related to the drug supply being toxic.

“We share that information with them either through our contacts with other agencies that have one-on-one interactions with those individuals,” he continued, “or, as in the case last week, where we had to publish a public alert to make sure people are aware that the risk is significantly elevated.”

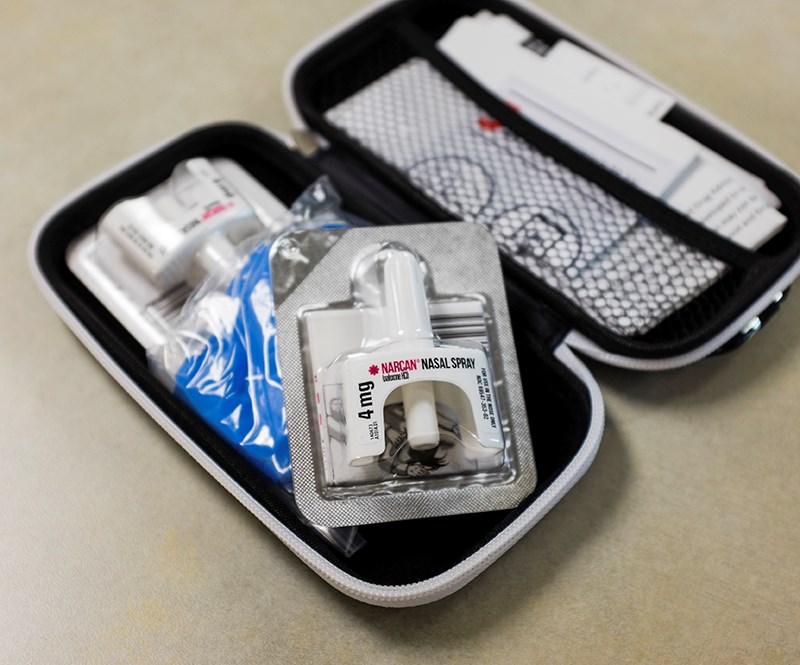

NARCAN + NALOXONE USE

We're using Narcan two, three times a week at The Lodge and overflow [shelter] and we've had some cases where it's taken four or five doses.

Myles Vanni

In 2023, LPH and community partners distributed nearly 4,300 naloxone (Narcan) kits; the life-saving medication can temporarily reverse the effects of an opioid overdose and allow time for medical help to arrive. Free kits are available from LPH, local pharmacies, and partner agencies including Community Health Centres.

The Sarnia Police Service recently began tracking how often naloxone is administered by officers on each shift; all front line officers now carry naloxone as part of their first-aid kits.

“Since April 22, 2023, the Sarnia Police Service has administered Naloxone on 17 occurrences,” Dep. Chief Julie Craddock told The Journal. “We don’t have data on the number of doses that were administered during those interactions, but often [officers] will need to administer more than one dose.”

Meanwhile, at the Good Shepherds Lodge shelter in Sarnia, the medication is in high demand, said executive director Myles Vanni.

“Before COVID, at The Lodge, if we used Narcan once or twice a month, that was a big deal,” he told The Journal. “Now we're using Narcan two, three times a week at The Lodge and overflow [shelter] and we've had some cases where it's taken four or five doses.

“So it is pretty significant.”

HOMELESSNESS & AFFORDABLE HOUSING CRISIS

We're not getting people out of shelter into housing. So, it's leaving more people on the street because the shelter's full.

Myles Vanni

It’s not uncommon for people who use drugs to also struggle with securing safe and affordable housing and many in Sarnia-Lambton are left to navigate the already-stressed shelter system.

A recent EMS report noted 580 calls for patients with no fixed address in 2022, representing 3% of the service’s annual total call volume — that number had doubled from the previous year (281 in 2021); of those clients, 12% were experiencing a suspected opioid overdose.

“The homeless demographic has really changed. Typically, it would be somebody's lost a job, their house, and we put them up for a short period and get them housed,” said Vanni. “Now, we're seeing the majority have some kind of drug usage or addiction, and then add mental health issues onto it as well.” said Vanni.

In the wake of the pandemic, shelter numbers went from 30-35 people a night, to a peak of 270 in care and shelters, he added, "That’s come down, but not back to those kinds of levels. We opened hotel shelters and motel shelters.”

For those sleeping rough, options like couch surfing have shifted even after pandemic restrictions have lifted.

“Once COVID hit, people said, ‘I can't have you in my home; can’t have you on my couch or in my basement. You're going to have to leave,’” Vanni said.

Over time, even as restrictions eased, folks were less willing to have people on their couch or in their basement, he explained.

“So some of those couch surfing opportunities just dried up.”

“We're not getting people out of shelter into housing,” Vanni stressed. “So it's leaving more people on the street because the shelter's full.”

The Inn created a rent supplement program which assists 35 people and a ‘Halfway to Home’ program, making arrangements with motel owners for a long term-lease for 25 clients. Without these programs, there would be about 60 more people in need of shelter every night in Sarnia, Vanni said.

The Inn is currently in the early stages of planning an affordable housing unit. The aim over the next year or two, is to build an apartment that can house 45-50 units; the focus is now on permanent housing solutions.

“[Drug addiction] has become a predominant feature in the clients that we're supporting through emergency shelter too. I'd say the majority of people that are homeless have some kind of addictions issue,” said Vanni. “And that's been a really difficult aspect for our staff who are used to being there to help people get them housed or help them find a job.”

With a lack of withdrawal management beds and no overdose prevention site in Sarnia-Lambton, people who use drugs often end up using alone in spaces like public bathrooms, leading to higher risk of overdose.

STRESS ON STAFF

Is somebody going to [overdose] and I'm not going to catch it on time?

“[Staff] come in at night, in the daytime, not knowing if they're going to find somebody in the bathroom in an overdose situation that they've got to revive,” said Vanni. “We're also dealing with a lot of people trying to smuggle drugs in, bringing paraphernalia in and using drugs in the shelter. They'll sneak it in and they'll be caught on their bed or caught in the bathroom using, which puts our staff really at risk as they walk into the bathroom, they might get a puff of fentanyl smoke or that sort of thing.”

Burnout in qualified staff across agencies and organizations in Sarnia-Lambton due to ongoing threats of violence and traumatic work environments is growing, officials say.

“It becomes a really difficult thing for our staff where they're physically at risk from exposure and emotionally, mentally at risk because they have to revive somebody or are worried they may not be able to,” said Vanni. “We haven't lost anybody yet at either the overflow shelter or The Lodge, but that's now top of mind sometimes for staff coming in — is somebody going to [overdose] and I'm not going to catch it on time?” said Vanni.

He adds that drug use typically leads to changes in character, with many becoming far more aggressive in their interactions with staff and other clients.

“There's too much risk to other clients and to staff, so, as much as we hate to say ‘you can't come in,’ we have a duty to protect the people we have in shelter.”

INTERACTIONS WITH POLICE

“We have more interactions or calls to the police to have somebody removed because of their aggression, but not everybody who uses drugs becomes aggressive,” Vanni explained. “Some people just sleep it off or go for a walk and then come back in an hour.”

He said one positive improvement has been the addition of the MHEART (Mental Health Engagement and Response Team), launched in 2019 through Sarnia Police, Canadian Mental Health Association and Bluewater Health.

“If they come to The Lodge, they talk it through, let the person walk around and just try to de-escalate it. The team… are supportive of the individual and try to help them come down rather than just looking at it from an enforcement point of view. The Inn is a place of second, third, fourth, and fifth chances,” he added. “So we may say, please remove this individual, but when the drugs have gone through their system and they are more cooperative — of course they can come to the shelter.”

DRUG FREE SHELTER POLICY

It's pretty traumatic when you see somebody die — you know, basically die, right?

Audrey Kelway

River City Vineyard shelter manager Audrey Kelway said drug use and overdoses reached crisis levels in recent years — so much so, that the Mitton Street facility moved to a zero-tolerance module with clients subject to random urine tests.

“When the pandemic started, it just got worse from there,” said Kelway. “We had people going into our washrooms and overdosing and we were using a lot of Narcan kits to save them and calling ambulances.

“There were people yelling at us and it was very, very stressful for the staff,” she added. “I lost one of my staff members because she couldn't do it anymore; she was a great worker.”

Kelway said there’s been some backlash since the policy-change, but most have been understanding.

“Some of our guys who were wanting to get clean and were doing quite well, would get tempted because we had people that would be dealing and coming to the front doors,” she explained. “Then, we realized that some who had gotten clean for a little while, were being tempted and were using. And that kind of broke our hearts, because they were trying so hard.

“So, we decided to become drug free in the front part of our building. We realized, for the people who really wanted to be drug free, we needed to give them a place where they would be able to be drug free.”

River City Vineyard’s shelter space is divided into two sections; the front has 28 beds reserved for people living drug free, subject to passing random urine tests. The back of the building provides shelter for people still using drugs — 25 beds for men and 16 beds for women.

“We are having to turn more away from the [sober] side of [the shelter] because we don't have the room on our [sober] side. So they will have to stay in the back and wait for a bed to become available. So if anything, we wish we had more [sober] beds,” said Kelway.

“[The shelter] is doing a lot better just because we're not having the trauma of having to deal with saving people. Like, you know, bringing them back to life. I mean, it's pretty traumatic when you see somebody die, you know, basically die, right?”

There is now a security company working with the shelter to assist with opioid-related emergencies and handing out sharps containers.

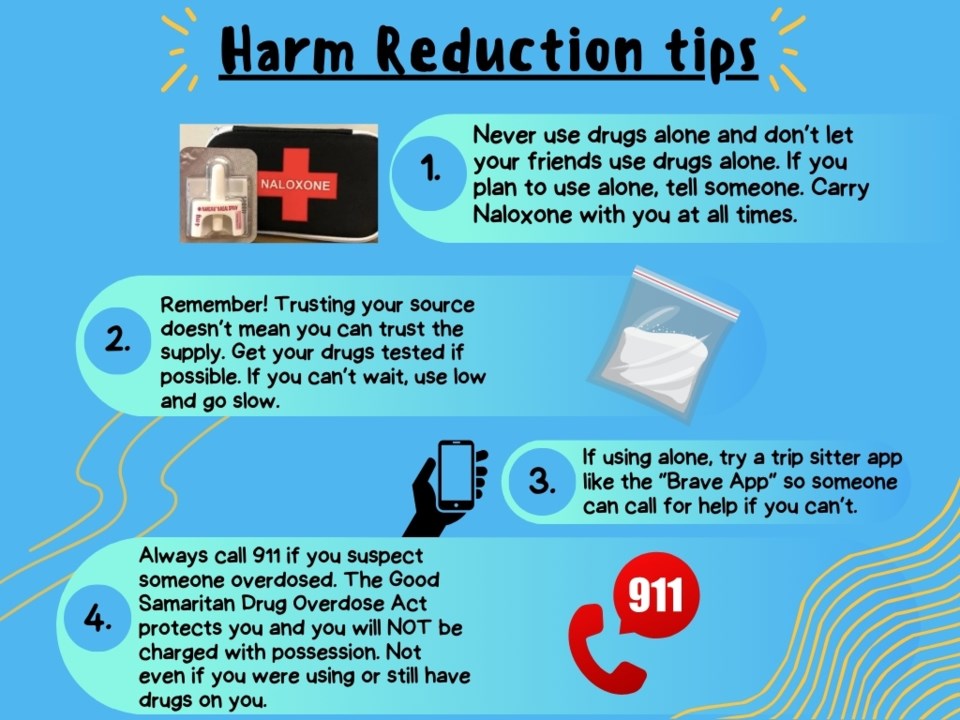

A HARM REDUCTION APPROACH

Incorporating harm reduction into local agencies and organizations is paramount, said Kal Larocque Lines, Outreach and Trans Support Worker at Diversity ED.

“You've already built those relationships with those people. People feel comfortable with you, and are able to ask you for help in those kinds of situations,” he said.

“During the adult Trans Support Group, I really believe in… talking about usage and not creating a stigma around it or attaching shame to usage.”

For people who use drugs, especially within the queer and trans communities, accessing the health unit for Naloxone, sharps kits or clean supplies can be a barrier to access, he explained.

“Even just walking in that building sometimes can be intimidating for somebody who is gender nonconforming or [misgendered] while accessing resources there,” said Larocque Lines.

“I've had clients say ‘I don't even want to tell my dentist about my sexual identity.’ When you go to Lambton Public Health there's that assumption that you're going to have to self identify, you’re going to have to do all this stuff, when it's realistically super easy and you don't have to fill out any kind of paperwork.”

FULL TIME STREET OUTREACH NURSE

In 2022, Lambton County hired its first community/street outreach nurse, who brings harm reduction supplies and Narcan to the streets for the homeless and underhoused, rather than relying on them to find medical support on their own.

“It’s a huge amount of service she is providing,” Gorgey said of Jennifer Gibbs who has been on the job since Nov. 2022, and had more than 2,000 engagements with clients on the street — assisting them with access to urgent and non urgent-primary care and with connecting them to resources like food banks and shelter.

“[The Street Outreach Nurse] has been a fantastic addition to our programs to try and reach those very vulnerable populations,” said Gorgey.

SEE MORE: What is harm reduction? [VIDEO]

HARM REDUCTION OUTREACH TEAM

“Living in a state of scarcity can make it difficult to prioritize health.”

The North Lambton Community Health Centre Outreach team serves all of Lambton, including the rural parts of the county. They provide services to people at street level to offer care and support, meeting clients where they are at.

“We know that the judgment and stigma directed at people who use drugs leads to a lack of connection with community and health care supports, including putting off seeking medical care for issues until they become emergent. This can lead to increased strain on the healthcare system, and poorer outcomes for the client,” said Nurse Kristin Lichty, of the harm reduction outreach team.

“At the center of our work is the acknowledgement that people who use drugs; people experiencing homelessness; and people who have been criminalized for their substance use are often fighting daily to have their basic needs met. Living in a state of scarcity can make it difficult to prioritize health,” she explained.

WITHDRAWAL MANAGEMENT BEDS

Bluewater Health's Mental Health & Addiction Services offers an inpatient unit, and a number of outpatient programs and services located both in the hospital and off-site. These include community treatment orders, crisis intervention, social work, assertive community treatment, and addiction and problem gambling services.

However, it will be at least 2025 before Sarnia-Lambton’s new 24-bed withdrawal management facility opens at Bluewater Health, despite a provincial announcement in 2022 that promised $12.5 million for additional early-stage recovery beds. Back then, the hope was that a new facility or “addictions hub” would open in 2024 to ease the community’s dire situation.

“With the delay of the withdrawal management beds, it's just lengthened out our ability to move people out of the shelter,” said Vanni.

Gorgey acknowledged the news was a ‘setback’ for the community but pointed to other community resources existing and working.

“Do we want more? Yes. And we are going to continue to push to have more opportunities for services and we are looking forward to the opening of the [withdrawal management beds] service as soon as it can.

“I think it will be a great day when it finally opens.”

LAMBTON DRUG AND ALCOHOL STRATEGY

A new Alcohol and Drug Strategy was announced last year by LPH, to complement other initiatives and resources. It brings together experts from 23 local agencies who will determine what more can be done and find a “Lambton solution” Gorgey told The Journal at the time.

The strategy is a 10-year plan that won’t solve the problem overnight.

“We have three individual action tables focusing on demand reduction, harm reduction and supply reduction,” said Gorgey. “We had a large meeting with all of those groups to develop their outcomes and what they think they can achieve in the first year. Now, that work is back in their hands to develop operational plans,” he explained.

“Once those plans come back to the steering committee then it’s our job to give them the resources they need to get the job done,” he said. “We are going to look at the issue around stigma within [the strategy] and I think even for organizations — it’s a really challenging concept to move that bar of what are health issues, and these are health issues and we need to treat it as such.”

STIGMA OF VISIBILITY IN COMMUNITY

Seeing more folks living on the street can be uncomfortable — even jarring — for those here who didn’t see it much before now, Gorgey explained.

“It is something that is new, and it can be challenging for people to see how they can help.”

He suggests more people view from an empathetic lens: “It’s going to be a challenge as a community that needs to take it on as ‘how can we be an empathetic community? How can we be a responsive community and see people for people?” If someone looks like they need help, that we can go and try to help them.”

LOOKING AHEAD

I think we just need to remind ourselves that [people who use drugs] are our neighbours, a lot of them grew up here, and these are people we know and we should feel for them and try to help them as best we can.

- Michael Gorgey, LPH

Officials are seeing more collaborative efforts between service-providers in Lambton, working together to support people who use drugs and alcohol," Lichty said.

"We’re hopeful that this increased connection and collaboration between agencies will help clients access the resources and supports available in our community. The more connected and aware we are of what’s available in our community, the better able we are to offer support."

“Time, understanding and work from all the agencies and faith groups, municipal leaders, business leaders, opinion leaders in the community all rallying around Lambton being a welcoming community that takes care of its people,” Gorgey concluded. "I think we just need to remind ourselves that [people who use drugs] are our neighbours, a lot of them grew up here, and these are people we know and we should feel for them and try to help them as best we can."

MORE ON HARM REDUCTION AND TIPS FOR THOSE WHO USE DRUGS:

Lambton Public Health Harm Reduction program, info & resources: https://lambtonpublichealth.ca/health-info/harm-reduction/

The Brave App (https://www.brave.coop/) is designed to connect people at risk of overdose with the help they need: an ally you can talk to, a human supporter to help you stay safe, and digital monitoring technology to help you when you’re in danger. The Brave App is not a substitute for calling 911.

To contact the writer, email [email protected]