Peter Fisher, of Passingham Drive, points to a deck built on a public right-of-way near Bright's Grove. Glenn Ogilvie

The question of who can use Sarnia’s “private” beaches has long been a legally murky one.

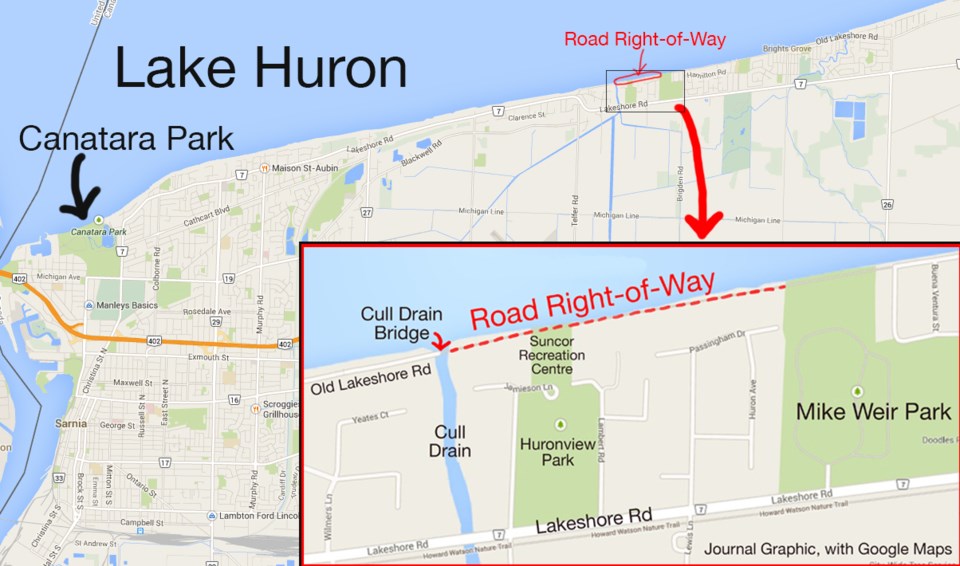

But it’s arisen again now that city hall is looking to reaffirm public ownership of an unmaintained right-of-way near Bright’s Grove, a move that could create a recreational trail to a half a mile of Lake Huron beachfront.

Peter Fisher is one of about two dozen property owners between Mike Weir Park and the Cull Drain Bridge who aren’t thrilled about the prospect of crowds arriving on “their” waterfront.

“It’s so easy to say, ‘Let’s build a path out here.’ But it’s not easy. It’s a dilemma and I don’t know how you resolve it,” said Fisher, who showed a Journal team around his property.

“It’s a beautiful beach and I’m lucky to have it. But we’ve got real issues here.”

The key issue is a 66-foot right-of-way that lay beneath Old Lakeshore Road until it was washed into the lake by a violent storm in 1973.

Once the “new” Lakeshore Road opened inland to reconnect Sarnia with The Grove, the former Sarnia Township left the property owners to fend for themselves.

Over the past 40 years they have installed their own expensive shoreline protection, and built fences, decks and boathouses on the right-of-way. In fact, almost nothing remains today to suggest a public road ever existed here.

Fisher points to a steel seawall at the bottom of his Passingham Drive yard. Half of the right-of-way is above the wall in his backyard and the other half in on the beach, he said.

Fisher doesn’t dispute Sarnia owns the old road allowance. But his deed states that any land between the right-of-way and the water’s edge belongs to him. As a result, anyone could use the beach in front of his house, but they would have to cross a narrow strip of private property to reach the water.

“I can’t stop it,” he said. “But what if something happened? Who is going to cover the liability for that?”

The law governing beach rights in Sarnia dates to 1830 when Samuel Street purchased more than 14,000 acres of land in what is now north Sarnia.

The deed granted Street ownership to the water’s edge, but it also stipulated there be “free access to the shores of Lake Huron for vessels, boats and persons.”

That wording was tested in 1987 when Sarnia resident Vic Ruzicic plunked himself down on a “private” beach east of Murphy Road.

He was soon confronted by the homeowner and asked to leave. Ruzicic refused, police were called, and he was charged with failing to leave when directed.

A Justice of the Peace found him guilty and imposed a fine. On appeal, a provincial court judge ruled the landowner did have property rights to the water’s edge.

But the judge also said Ruzicic “reasonably believed that he had an interest in the land through the Crown reservation in the original grant.”

The charge was dropped.

Today, it’s generally understood that Sarnians have a right to walk on private beaches so long as they don’t settle down and stay there.

Last week, council directed city staff to determine the property lines and check the titles and deeds on Sarnia’s “lost” beach. Staff will also estimate the cost of building a multi-use path for walkers and cyclists on the waterfront right-of-way between Weir Park and the Cull Drain Bridge, as well as shoreline protection and maintenance.

A full report is expected this fall, when councillors will decide whether to repair or replace the bridge, which was closed two years ago for safety reasons.

Meanwhile, Fisher said, some property owners are prepared for a fight.

He spent $10,000 securing his shoreline with rock-filled baskets, and other neighbours have invested up to $100,000 on engineering, massive blocks and steel breakwalls, he said.

“We have spent a lot of money saving the waterfront for the city. Let’s leave things the way they’ve been for 40 years, and leave it that way for the next generation.”

- George Mathewson